Capturing complexity of capturing carbon

Thoughts and words that escaped my Climate & Capital Media article

Hey Power Japan readers,

Acute crises and drawn-out structural shifts. These are the two ends on the spectrum of global affairs.

Notoriously, the media swarms to the former. And who can blame them? From the twists and turns in tariff talks, Russia-Ukraine negotiations, to the Israel-Hamas war, the world today feels rife with the acute and the urgent.

But the slower and deeper changes are often equally, if not more, momentous. I think elements of Japan’s energy diplomacy are among those important trends.

My recent piece in Climate & Capital Media takes stock of one such strand — Japan’s carbon capture and storage strategy.

Simply summarizing my article won’t be any fun (for you or for me), so I want to share with you a few quotes from my interviewees that didn’t make it into the final piece. For color, yes, but also for a better understanding of the nature and implications of Japan’s CCS strategy.

Did you have a chance to read my July contribution to the East Asia Forum on Japan’s metamorphosis from an LNG buyer to merchant? I also wrote a summary of the article here:

Oh, and my PhD dissertation will finally be published as a monograph titled Financial Regulators and Macroprudential Policy (Routledge) in September. I’ll have more to say about this in a future post.

If you have informed and considered opinions on the merits of carbon capture & storage as a decarbonization solution, I’d love to hear from you. And if you have useful resources to better understand this technology and the issues surrounding it, please consider sharing.

CCS inside & outside Japan

“Japan has been trying to promote CCS for many years already,” said Ayumi Fukakusa, Executive Director of the campaign organization FOE Japan. “Exporting CO2 is a vital part of their decarbonization plan [because] they need storage outside the country.”

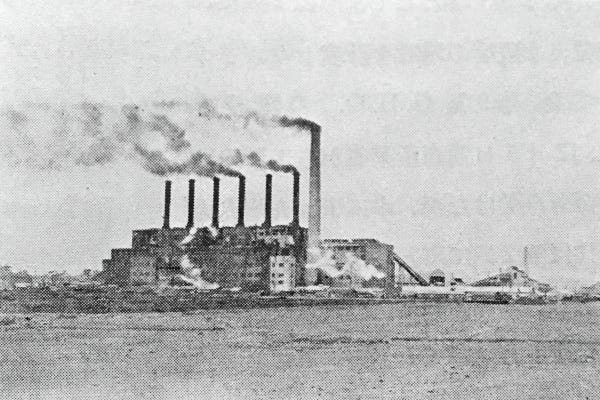

Let’s back up a bit. Why does Japan need CCS? Mainly because Japan’s energy roadmap for 2040 will still include a big use of fossil fuels — including coal — both for power generation and in the industrial sector. We’ve talked at length about this before:

The Japanese government and energy companies talk a big game about “zero emission thermal power.” In plain language, that means reducing emissions from fossil fuel power plants. That includes installing CCS infrastructure on power plants, along with mixing fuels like hydrogen and ammonia.

Japan’s CCS push is consequential not only for Japan itself, but also for the Asia-Pacific as a whole. Analysis by the energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie makes it easy to understand why. It expects Japan’s CO2 capture capacity to reach at least 55 million tons per year by 2050. To put that into context, that’s about the same as the entire global carbon capture capacity in 2023. Japan has nowhere close to enough storage space underground for all of that carbon domestically, nearly 80% of it will be sent overseas to be injected underground. To put it bluntly, Japan will be the leading exporter of carbon emissions to neighboring countries in Asia for sequestration.

This is simply hot potato from a carbon accounting perspective. Grant Hauber, energy finance advisor at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) characterized it like this: “Ideally what Japan wants is to get that carbon off their carbon balance sheet and transfer the responsibility to Malaysia and Indonesia, who then take ownership. And that goes on their balance sheet.”

Why countries like Indonesia and Malaysia want to import Japan’s CO2

What I’m always curious about is this: What are the motivations of Japan’s partner countries to work with Japan?

Alex Zapantis, strategic advisor to the Global CCS Institute (a think tank and industry interest group), helped me understand this better. South and Southeast Asian economies are growing. Generally speaking, growth, energy use, and carbon emissions go hand in hand. “The simple reality is that if they [Southeast Asian countries] don't have CSS, it's impossible for them to achieve net zero,” he told me. “In fact, it's simply impossible for them to even stop their emissions growing.”

There are also reasons not related to emissions reduction. For emerging economies of Southeast Asia, taking part in Japan’s CCS strategy comes with beneficial strings attached. Zapantis went on to explain that “Japanese support, Japanese direct investment, Japanese firms going into joint venture, doing the studies that are necessary to understand how to build projects, and sharing that technology is critical to enable anyone to invest in CCS in these countries.”

Japan is historically a leading provider of overseas development aid and direct investments in the region, which explains why countries of Southeast Asia hold Japan in high regard.

Another motivation I hadn’t thought of before is a broader, forward-looking strategy of attracting future industrial investments to Malaysia and Indonesia. Again, Zapantis:

if you build infrastructure in the right places where there are already industrial clusters of industries, you can create CCS hubs, right? So down the track, if you're about to build your next your brand new steel facility and you're looking around the world, … one of the things you're going to be looking for is … “do I have a CO2 management option?”

In other words, because companies in the industrial and heavy manufacturing sectors are under pressure to reduce emissions, they’ll target area where they can easily capture their emissions when considering future facility construction. Places like Malaysia and Indonesia are trying to become competitive candidates for these types of investments.

But where does the money come from?

The oil and gas industry has captured carbon emissions for decades. But they’ve done this because they would inject that captured carbon into oil and gas wells to produce more fossil fuels. Enhanced oil/gas recover, as it’s called, is profitable.

On the other hand, there is no profit to be found in permanently storing away carbon. Like any waste reduction or pollution control, carbon emissions are an externality. It’s the role of public policy — carbon price, carbon markets, subsidies, etc. — to attach value to CO2, which will incentivize companies to build CCS infrastructure and to capture their emissions.

That brings us to the question: what policies or mechanisms are making Japan’s CCS deals financially viable? This is a far more complex topic than I can do justice to in this post, but let me try to hit the main points.

Here, the timeline matters. In the short term, the CCS projects that Japanese companies are currently studing in Southeast Asia won’t be profitable. Zapantis was blunt on this point:

How does it create financial value? At the moment it really doesn't. The business model in Southeast Asia is really difficult because you don't have a carbon price, at least not a material one. You don't have subsidies or capital grants like you have in Europe and North America, where the governments can afford to tip billions to enable those investments to proceed.

Japanese firms developing these projects do benefit from subsidies from the Japanese government and government-backed agencies like JOGMEC.

In the longer term, it seems that the Japan-led “Joint Credit Mechanism” (JCM) will be the secret sauce that makes CCS work. JCM is a bilateral carbon credit system, where Japan carries out emissions reduction activities in a partner country and credits the partner country for the avoided emissions. Japan and Malaysia are aiming to start a JCM partnership this year.

How the JCM and domestic carbon pricing in both Japan and partner countries might interact is not clear to me. That’s a topic for future investigation.

What worries me

Well, many things worry me about Japan’s CCS strategy. I’ll raise the most serious ones here.

Capturing and storing carbon is not an airtight process — at all. IEEFA’s Grant Hauber explained this to me in detail.

Compressors emit a certain percentage of their compressed product regardless of what it is. Pipelines leak. Joints. Valves. Everything has a leakage rate. If we're going to do shipping from Japan to hapless customers in Indonesia and Malaysia, you have boil off, you need recovery systems, you have induced risks of losses at transfer on board and off board ship accidents.

Not only does CO2 leak all throughout the value chain — CO2 can corrode the equipment it’s in. “In the presence of any moisture, CO2 forms carbonic acid,” Hauber said, “which is immediately attacking the metals that you're trying to hold or transport this CO2 in. It can eat away at cements and joint compounds and all sorts of stuff.”

Geologic storage — the process of permanently storing CO2 underground in saline aquifers, depleted oil and gas reservoirs, basalt formations, etc. — is mind-bogglingly complex. Every storage site is unique and must be studied to death to make sure that carbon doesn’t move around underground or, worse yet, leak into the atmosphere.

Here’s Hauber again, worth quoting at length:

the thing with CCS, if you are truly banking on it as a nation and as an investor to be a decarbonization solution, it has to be a permanent solution… There are no acceptable losses in CO2 disposal, especially once it's in the ground, because it's more like nuclear waste management than hydrocarbon management. Any leakage rate means you're eventually going to get it back in the atmosphere, and that negates the whole purpose of it.

Hauber adds that “I have not seen the level of rigor, disclosure, detail, planning, press releases, papers on any of the other major proposed sites in the world,” including those in Indonesia and Malaysia. I haven’t seen any announcements of such studies, either.

Anything that needs to be managed permanently begs the question: Who’s going to do it? That’s when the issue of liability encroaches into the CCS conversation. Presumably, the CCS operator will handle the constant monitoring, maintenance, and damage control. But what if that operator goes bankrupt?

Japan’s CCS Business Act requires project operators to monitor storage conditions. Once the stability of the stored CO2 is confirmed, the responsibility is handed over to JOGMEC, with the implication that the agency will monitor and maintain the storage site in perpetuity. “If you’re in an economic crisis or you’re constrained on fiscal resources, if you haven’t provisioned for it, what happens to that CO2?” asks Hauber.

These were illuminating conversations. I hope they give you a sense of just how massive an undertaking it is for governments to rely on carbon capture for their decarbonization pathways. For my part, they left me with more questions and caution than conclusions.

Okay, this post is already far longer than I intended. Thank you as always for reading Power Japan. See you next time.

What are your thoughts on CCS, either in Asia or elsewhere? What resources are helpful in learning more about it? Share them in the comments or in the subscriber chat.