Power Japan Newsletter - Energy Efficiency, Ugly Truth about Climate Finance, Hydrogen Strategy, CCS and more

Hi all. This is the 2nd installment of the Power Japan Newsletter. There’s a lot happening in the world of energy in Japan and in the world. I picked out a handful that may not have been on your radar, explain them, and offer some commentary around the political economic dynamics surrounding them.

If you like this newsletter, the best thing you can do is to subscribe. I’d also be delighted if you repost it, comment on it, or simply “Like” it. If you have suggestions or questions, please comment at the bottom of the newsletter or send me a message.

On the Global Stage

Global greenhouse gas emissions reach “unprecedented” levels

Sorry to start with bad news, but we need to keep our eyes on the prize: the prize of limiting anthropogenic (human-caused) global warming. 🔬 A study published in the journal Earth System Science Data shows that human-induced global warming has been increasing at an “unprecedented rate” between 2013-2022. This is despite a sharp fall in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in 2020 when the COVID-19 lockdowns diminished economic activity in many countries.

The fact that the world is emitting more GHGs means that we are running out of “carbon budget.” Only about 250 billion tons of CO2 can now be emitted, down from 500 billion tonnes just a few years ago. To grossly simplify, this means that if the world emits 250 billion more tons of CO2, we cross over into 1.5C° warming.

We are now living in the pivotal decade. According to the lead author of the study, “This is the critical decade for climate change. Decisions made now will have an impact on how much temperatures will rise and the degree and severity of impacts we will see as a result.”

One piece of good news: “there is evidence that increases in greenhouse gas emissions have slowed,” and depending on societal choices, we could see a change of direction for human influence on climate over this critical decade.

Those societal choices are happening, slowly and in small doses, but surely. Let’s talk about some of those choice that happened in the last 2 weeks.

45 governments commit to doubling global energy efficiency…

On June 6-9, the International Energy Agency hosted the 8th Annual Global Conference on Energy Efficiency in Versailles. The conference brought together 32 ministers, more than 50 CEOs and other senior leaders from 90 countries (including Japan) to accelerate progress on energy efficiency that’s needed to address today’s global energy crisis and pressing climate imperatives.

Energy efficiency doesn’t grab headlines. But it’s critical tool in the fight against climate change - by reducing overall energy consumption, we reduce demand for fossil fuels and greenhouse gas emissions. Importantly, improving energy efficiency also has a number of other societal benefits. It can create jobs (12 million jobs by 2030), support progress toward universal access to modern energy around the world, reduce energy costs, decrease air pollution, and strengthen countries’ energy security by diminishing their reliance on fossil fuel imports. In the words of the IEA Executive Director Fatih Birol, “It’s hard to overstate the importance of energy efficiency for strengthening energy security and keeping the goal of limiting global warming to 1.5C° within sight.”

The IEA also unveiled a report titled Energy Efficiency — The Decade for Action at this conference, which highlights the importance of energy efficiency action in coming years. Examining recent trends relating to demand and policies, it highlights several global accomplishments:

Energy efficiency policies have strengthened globally in the past year as governments supported energy consumers, launching awareness campaigns to help reduce energy, and spending over USD 900 billion to shield consumers from rising energy bills.

Sales of key efficiency technologies are surging since 2022, including heat pumps and EVs. Efficiency investments are also set to reach record levels in 2023.

Thanks to these trends, rise in global energy demand has been limited to 1%. Without efficiency policies and technologies, this would have been ~3 times higher.

Building on this progress, the IEA urges these next steps for the improvement, implementation and investment required for an energy efficient future:

Doubling the efficiency improvement from 2.2% annually today to >4% annually by 2030. This would align with the IEA’s Net Zero Scenario, lower global energy demand by 190 EJ and CO2 emissions from fuel combustion by almost 11 Gt by 2030.

Governments must accelerate the implementation of all existing policies. If they do, they can deliver 3/4 of this doubling goal by 2030.

Tripling of annual efficiency-related investment from USD 600 billion today to USD 1.8 trillion by 2030 is needed to achieve the goal of doubling the rate of progress.

The report also updated the Sønderborg Action Plan that was first formulated last year. The Action Plan provides a practical approach to accelerate action on energy efficiency by guiding governments in the design of effective policy measures, the support of policy decisions and the delivery of policy actions.

…but wealthy countries’ climate finance is ending up in strange places…

In 2009 and again in 2015, wealthy countries agreed to spend $100 billion a year in helping developing countries reduce GHG emissions and build resilience against climate change. They’ve fallen short of this goal. But what’s more troubling is that a substantial minority of the funds they did spend went to projects that don’t even come close to fighting climate change.

Reporters at Reuters and Big Local News examined thousands of records that countries submitted to the UN. They found that developed countries reported more than USD182 billion between 2015 and 2020 in what they counted as climate finance. But:

There are no official guidelines for what activities count as climate finance and no uniform system of accountability. In the others of an undersecretary of the Philippines Department of Finance, “This is the wild west of finance. Whatever they call climate finance is climate finance.”

Because of this, a large portion of the money goes to projects of questionable climate impact or completely irrelevant for climate. For example, Italy’s climate finance helped open chocolate and gelato stores across Asia, the US extended a loan for a coastal hotel in Haiti, Belgium backed a film about a love story, and France reported a loan for environmental initiatives in China that was then canceled. Each country counted these funds as part of their climate finance contribution.

Japan is the largest contributor of climate finance in the world, totaling USD 58.8 billion and accounting for nearly 1/3 of all climate finance pledges. And yes, Japan is implicated heavily in this story, with questionable projects including:

Airport in Egypt. USD167 million loan for rooftop solar panels on a planned airport terminal in Egypt’s Borg El Arab airport. This will increased outbound flight emissions by ~50% over 2013 levels.

Coal plant in Bangladesh. A new 1,200 MW coal-fired power plant in Bangladesh, which will add 6.8 million tons of CO2 to the atmosphere per year

And more coal plants. 3 more coal plants, one in Vietnam and two in Indonesia

USD 3 billion for energy projects that rely on natural gas

This overall finding is consistent with the data compiled by Oil Change International, an advocacy organization. According to this database, Japan is the largest public-backed funder of fossil fuel projects internationally, at USD 9.6 billion.

This article left a deep impression on me. Climate finance has been a fraught issue in climate negotiations between wealthy and developing nations for years. Each time wealthy countries agree to commit billions of dollars in climate finance, be it in Kyoto in 2009, Paris in 2015, or Sharm El-Sheikh last year, there’s renewed hope that societies that industrialized thanks to fossil fuels will help other economies grow without contributing to global warming. Yet each time, wealthy countries fail to deliver the sums they promised. This report casts a new shadow on this reality.

How can we ensure that financing countries are directing funds to projects that truly mitigate GHG emissions or help developing countries adapt to the changing climate? The short answer is clear definitions, international guidelines, and more transparency. But it’s easier said than done. I invite you to read the Reuters article to learn why.

In and Around Japan

Government revised the “Basic Hydrogen Strategy”…

On June 6th, the Japanese government revised the "Basic Hydrogen Strategy" for the first time in six years.

Hydrogen doesn’t emit CO2 when it’s burned and can be used as an energy carrier. For these and other reasons, hydrogen has a potential to reduce emissions in a wide range of sectors.

In 2017, Japan became the first country to formulate a national strategy for hydrogen power, aiming to drastically scale up its use by 2030. Since then, with Japan’s own declaration of carbon neutrality by 2050 and the energy market shock caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, there’s been growing interest in hydrogen as an energy source. The US, EU, China, India and Australia have also put forth their own hydrogen strategies since 2017.

Given this context, the Japanese government revised the Basic Hydrogen Strategy. The utilization of hydrogen is also one of the pillars of the GX that the national legislature recently passed. The main gist of the revised strategy are:

Designate 9 strategic areas, including electrolysers (technology that produces hydrogen from clean energy and water) and fuel cells, as sectors to be developed

Direct over ¥15 trillion (USD 106 billion) in private-public investments over the next 15 years;

Increase hydrogen use to 3 million tons by 2030 and ~12 million tons by 2040 (~6x the current level).

Yet, doubts about the new Hydrogen Strategy remain:

Most hydrogen is dirty. Today, less than 1% of the global hydrogen supply is produced using low-emission methods, which means that throughout its value chain, hydrogen doesn’t contribute to emissions reduction. Investments in hydrogen supply chains that originate in renewable energy is critically important.

Japanese government is silent on “green hydrogen”. The revised Japanese hydrogen plan does not offer a target for the amount of clean hydrogen (derived from renewables or nuclear power). The government is focused on simply producing more hydrogen, even if it’s fossil fuel-derived. But since the value chains for fossil-derived and renewables-derived hydrogen are fundamentally different, the former can’t serve as a transitional step for the latter.

Can the Strategy be implemented? The government fell short of achieving some of its 2017 goals. It said it will establish around 100 renewables-derived hydrogen stations. It established 27. It aimed for 40,000 fuel cell cars, but there are only ~8,000 today. It wanted to reduce hydrogen cost to ~¥50,000 per kWh by 2020. That didn’t happen.

No better for energy security. The Strategy’s goal is to increase domestic hydrogen consumption, but it’s silent on domestic production. The assumption is that most of the hydrogen will be produced abroad and then imported. Joint ventures between Japan and Australian firms, for example, are already under way to build up this supply chain.

… and get serious about carbon capture & storage (CCS)…

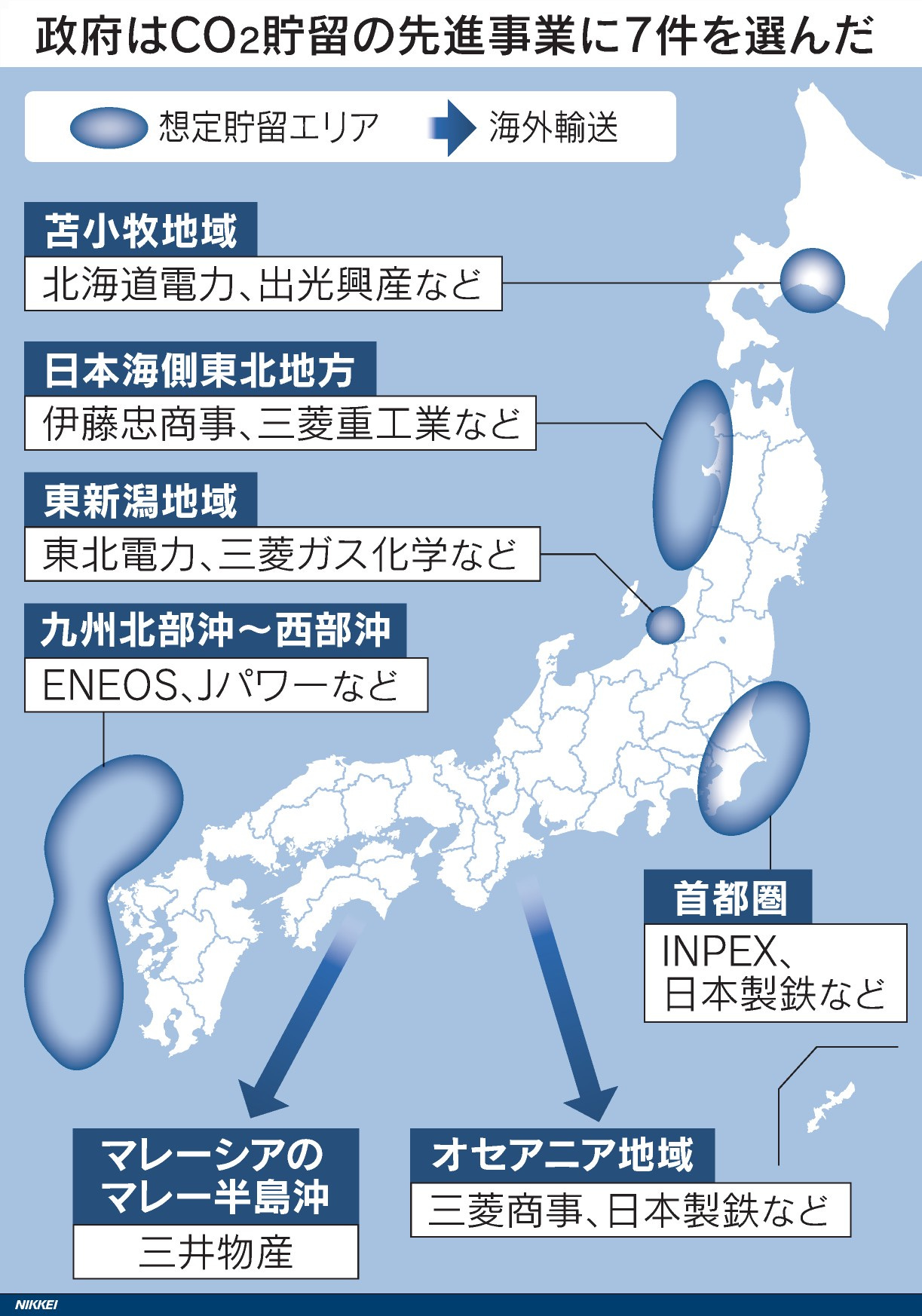

On June 13th, the Japanese Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry selected 7 projects as part of its initiative to develop CCS capabilities. CCS involves capturing CO2 emitted (mostly) from electric generation and storing it underground. Major energy and industrial companies like Hokkaido Electric, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Tohoku Electric, ENEOS, J-Power, and Mitsui are among the designated companies.

Storage sites: 5 domestic storage areas are Tomakomai, the coastal areas of northeastern Japan Sea, eastern Niigata, the Tokyo Metropolitan area, and offshore locations in northern Kyushu and western Japan. To these, 2 overseas areas are added: Malaysia and the Oceania region. See the image above ☝️

Liability and cost were bottlenecks. Companies and financial institutions have been wary of potential liability risks in case of CO2 leaking into the seabed, hindering CO2 storage capacity development. The government seeks to mitigate these concerns by providing subsidies for surveying costs, establishing safety measures, and proposing new legislation in 2024 to limit the liability of operators in case of mishaps.

Fraction of emissions. If these 7 CCS projects are successful, they’re expected to store ~13 million tons of CO2 annually by 2030. But this capacity only accounts for 1% of Japan’s annual emissions. The goal is to achieve between 120 million tons to 240 million tons of CO2 per year by 2050, which will account for 10-20% of domestic emissions.

According to the IEA, global capacity for CCUS (CCS plus Utilization) is expected to increase from 45.9 million tons of CO2 to 320 million tons by 2030. Most of this increase is set to take place in North America and Europe. With these 7 projects, Japan seems to be trying to squeeze into this future projection.

But I, for one, am sympathetic to criticisms of CCS. The Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis points out that in the long history of CCS, failed or underperforming projects outnumber successful ones. Even where successful, CCS serves “as a greenlight to extend the life of fossil fuels power plants.” Since many of the firms appointed to work on the 7 projects in Japan are also power companies, I’m concerned that these projects, too, will be used to prolong the life of thermal power generation.

… while Japanese Companies Push for Floating Offshore Wind.

Toda Construction in Japan has partnered with Osaka University to research whether floating wind turbines can withstand major typhoons, tsunamis and other natural disasters in the Goto Islands in Nagasaki Prefecture. This collaboration is part of an intensifying global competition to scale up floating offshore wind.

US and Europe are proactive. Series of measures and investments in the US and Europe aim to establish domestic supply chains and reduce electricity generation costs.

Japan’s needs are unique. Experts in Japan argue that the country’s technical needs are unique and distinct from those of the US and Europe, since the wind turbines off the cost of Japan must resist regular typhoons, earthquakes and tsunamis.

Yet Japan is aiming to be a first-mover. In the words of Hiroaki Kobayashi of Tokyo Marine & Nichido Fire Insurance, Japan “still have a chance to create the rules for floating offshore wind.”

Destination is the Asia market. The majority of the demand is expected to come from Asia, with its strong economic growth. The installed capacity of floating offshore wind power in Asia is expected to reach ~30 million KW by 2040 and surpass Europe.

Deep Investigations

From this edition of the Power Japan Newsletter, I try to include one or more research reports that go beyond the news. This week, I want to highlight a report on the possibilities of renewable energy in Japan.

Berkeley Lab. The 2035 Japan Report: Plummeting Costs of Solar, Wind, and Batteries Can Accelerate Japan’s Clean and Independent Electricity Future.

Many in Japan, including political and business leaders, believe that massive deployment of renewables in Japan is impossible because of geographic constraints. This report by the Electricity Markets & Policy at the Berkeley Lab asks 3 questions for Japan:

1️⃣ How recent declines in costs of renewables will affect the pace & scale of renewable resource development?

2️⃣ What clean energy goals are technically & economically feasible?

3️⃣ How can a faster clean energy transition benefit energy security?

Using granular spatial and temporal data, as well as latest renewable energy and storage cost estimates and trends, the report finds that, by 2035:

👍 Most importantly, scaling up renewables to achieve a 90% clean energy grid is feasible

⚡Japan’s 90% clean energy grid can dependably meet electricity demand with large additions of renewable energy (utility & residential #solar, onshore & offshore #wind) and energy storage, and without coal

📉 Clean energy deployment can reduce wholesale electricity costs by 6%

🚢 90% clean energy deployment can reduce fossil fuel import costs by 85%, bolstering Japan’s energy security

🌿 Clean energy can cut CO2 by 92%, providing significant environmental benefits

This study is just one of several academic and think tank publications that attest to the feasibility of massively scaling up renewable energy to cover most if not all of the energy demand in Japan. The remaining question is whether Japanese policymakers will heed these lessons

Did you like what you read? Subscribe, like, and share Power Japan. In addition to posting longer-form articles at a regular interval, my goal is to send out this newsletter every two weeks.

Have suggestions on what to include? Comment below or send me a message.

The views expressed on this newsletter/blog are mine alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of my employer.