Crafting an international hydrogen market

How Australia, Germany, Japan and Korea can cooperate

According to the International Energy Agency, there are now over 40 countries with national hydrogen strategies. If we look at the “National Hydrogen Strategies and Roadmap Tracker” compiled by Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Strategy, that number comes out to over 60. Whatever the exact number, the point is that there’s a lot of momentum behind hydrogen as a low-carbon fuel.

Many of these hydrogen strategies are aspirational. Pies in the sky. But in others, particularly in countries with well-developed industrial sectors, policymakers mean business. Real quantitative targets, real target dates, real frameworks, and real policies accompany their hydrogen strategies. Real hydrogen molecules, rather than empty talk, will be produced and consumed because of those strategies.

Most of those molecules, it’s safe to assume, will be made and used locally. Not only in the same country but in the same industrial cluster. That’s because hydrogen’s physical properties make it very difficult and energy-intensive to transport and store.

But some countries (like Japan, Korea, and Germany) envision that they need more hydrogen to decarbonize their economies than they can produce on their own soil. Other countries (like Australia) are expected to produce more hydrogen than will be consumed at home, or at least to sell much of that hydrogen overseas at a higher price than in their domestic market.

If the economics of its transport and storage can be solved, we’ll likely witness the emergence of an international hydrogen market. But markets need rules. Rules are predicated on agreements. So, what agreements are needed to facilitate international hydrogen trade?

An insightful report landed in my inbox that suggests an answer to this question.

The report was published last month by the Germany-based organization Adelphi. Adelphi is an independent “think-and-do tank” and public policy consultancy that works with national governments, international organizations, financial institutions and businesses on climate, environment and development. A part of its work is facilitating bilateral diplomatic partnerships in clean energy between Germany and many other countries, including Japan.

Their report “Status of Hydrogen and Potential for Cooperation” offers a comprehensive and up-to-date description of hydrogen policies, support measures, technologies and projects in Australia, Germany, Japan, and Korea. Adelphi chose these countries because of their existing and close diplomatic relations and, crucially, there is a potential for quadrilateral hydrogen trade between them. Australia is gearing up to be a major hydrogen producer, while Germany, Japan, and Korea will become major hydrogen importers.

What are the report’s recommendations on how these four countries could cooperate to establish hydrogen trade?

National hydrogen statuses

But before I get into the report’s proposals, I want to briefly highlight how useful its country-specific chapters are.

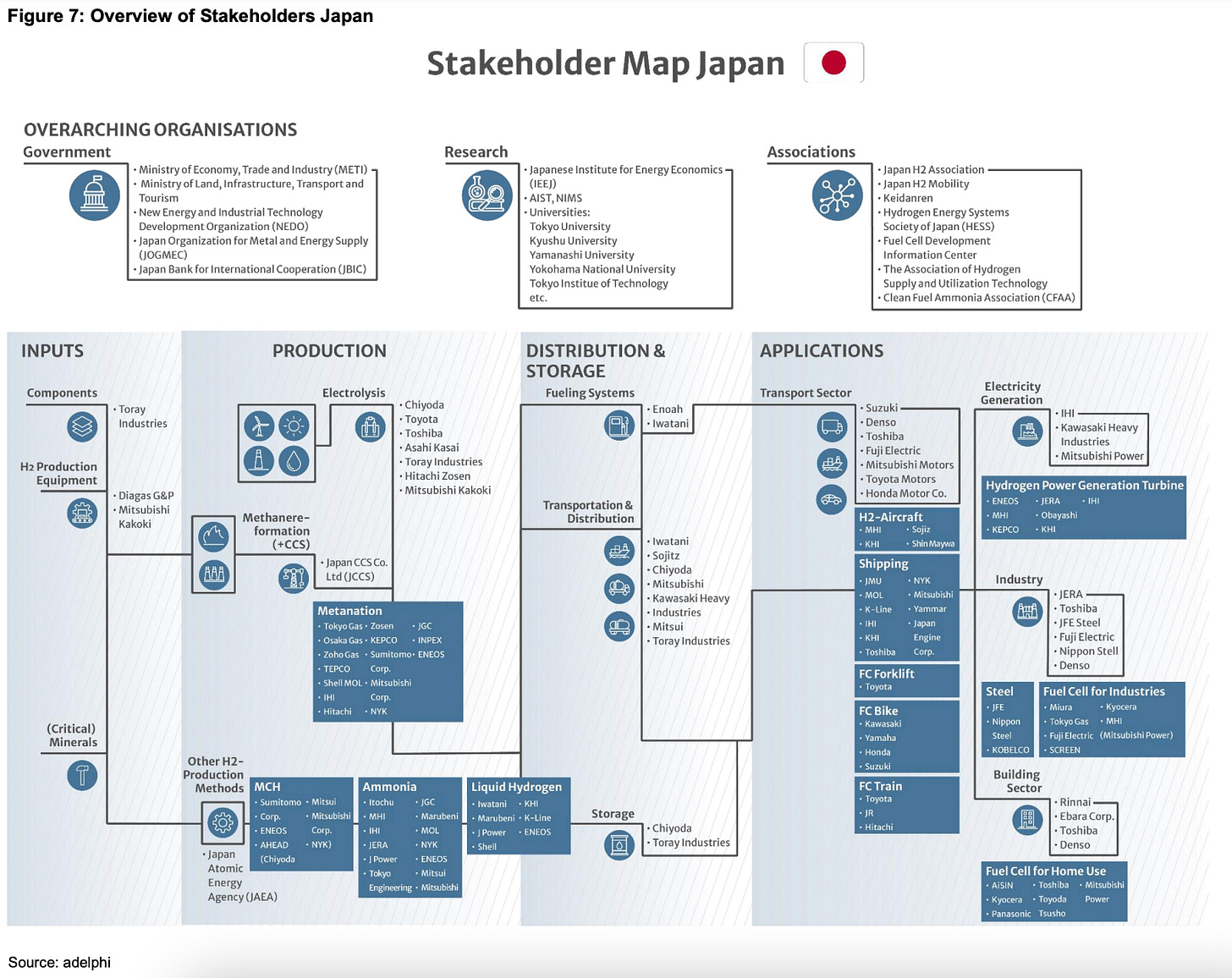

Drawing from publicly-available sources, the chapters on Japan, Germany, Korea, and Australia explain each country’s hydrogen strategy, specific policy measures, technological progress, and status of hydrogen projects. Anyone interested in an up-to-date look at hydrogen in any of these countries will learn a great deal.

Plus, for each country, Adelphi provides a phenomenal diagram of the stakeholders along the entire hydrogen value chain. The diagram for Japan looks like this:

Why multilateral cooperation?

Australia, Germany, Japan and Korea already have bilateral work streams on clean energy and hydrogen with each other. So why expand these ties to the multilateral level?

Adelphi has a good explanation:

the gradual multilateralisation of the hydrogen market offers multiple advantages … which in turn accelerate the much-needed technological progress, the reduction of market power asymmetries, where suppliers alone can set the trading conditions, reduced dependencies, and lower transaction costs. For Germany, Japan, and Korea, specifically, collaboration can mitigate competition for hydrogen supplies and instead establish trading patterns beneficial to all three countries, strengthening their overall position in the market... For Australia, collaborating with three of the biggest hydrogen importers and hydrogen-technology front-runners offers substantial business opportunities, not merely with regards to supply contracts but also in terms of the transfer of know-how and technologies.

In other words, multilateral cooperation will help importers avoid detrimental competition among each other, establish a level playing field with exporters, and help exporters access attractive markets and share knowledge.

Getting specific: topics of cooperation

Adelphi identifies 7 areas in which the four countries can increase their dialogue.1

1. Hydrogen transport

This is an obvious area of cooperation where the interests of all four countries should easily converge. Because each country aims to either export (Australia) or import (Germany, Japan, and Korea) hydrogen in the near future, discussions on the technologies and infrastructure developments needed for hydrogen transport should benefit everyone.

Japan and Korea are leaders in the design and construction of hydrogen transport vessels. Bringing together representatives from respective companies with port authorities in Australia and Germany can help identify the required adjustments to the port infrastructure. At the same time, port authorities and shipping companies from all countries can exchange their experiences and determine areas of collaboration.

2. Hydrogen safety

Hydrogen corrodes metals like steel and iron. It’s prone to leaking. It’s flammable and its flame is almost invisible. So, hydrogen safety is paramount.

there is a growing need for collaboration among port authorities, infrastructure developers, and policymakers globally to exchange insights and strategies on hydrogen safety. Establishing a coordinated approach, possibly through the formulation of standards, to delineate responsibilities for safety provisions at various points along the trading route up to the consumption centres could prove beneficial. Clarity on safety is a prerequisite for the implementation of projects to prevent harm to workers, the public, and the environment and to ensure social license.

3. Bankability of hydrogen projects

Bankability means making infrastructure projects attractive and predictable enough to secure financing from banks and investors. A bankable project is a financially viable project with a high likelihood of paying loans or generating returns on investments.

For new industries like clean hydrogen, making projects bankable is a high bar. That’s because hydrogen production facilities need access to resources (land, water, grid connections, transport, storage, and in the case of green hydrogen, renewable electricity), secure contracts with offtakers, keep production costs reasonable, among other things.

So how can Australia, Germany, Japan and Korea cooperate to enhance the bankability of hydrogen projects? The example Adelphi gives is collaboration among public and private financial institutions:

For instance, public and private finance institutions and banks from all four countries … could join forces to devise support options and scale up financial support for the hydrogen market ramp-up.

4. Workforce development

As in any new industry, the clean hydrogen economy needs skilled workers. Public-private initiatives can help foster and re-skill workers, either by shifting workers from existing industrial sectors or people who are newly entering the workforce. Adelphi points to the example of the “Careers for Net Zero” campaign by the Australian Council for Clean Energy and Energy Efficiency Council aimed at encouraging more people to move into energy transition-related jobs.

Policy-makers from all four countries may exchange their respective approaches to this and might want to consider setting up exchange programmes for workers to benefit from each other’s strengths.

5. CCU/S technologies

It seems that most of the hydrogen projects being planned or under development today will be producing blue hydrogen (made with fossil fuels with the use of carbon capture, utilization and storage). I’ve had my share of gripes with this trend, but it’s reality.

Adelphi points out that “even Germany, who has always been rather hesitant towards the usage of CCU/S technologies, has developed a carbon management strategy to regulate the handling of unavoidable or difficult to avoid residual emissions, and allows for the import of blue hydrogen, even though funding still clearly concentrates on green hydrogen.”

It goes on the recommend that, “To ensure transparency and the responsible application of CCU/S technologies, creating an open dialogue and robust policy framework between the four countries on this issue can be useful.”

6. Hydrogen in the electricity sector

All four countries are preparing to use hydrogen in their power sector. As Adelphi explains:

South Australia has recently kick-started the process for the construction of a hydrogen power plant in Whyalla ... Meanwhile, Germany foresees a key role for H2-ready power plants in its newly announced power plant safety act. Korea plans to commercialise electricity generation from hydrogen and ammonia by 2027 and has introduced the world’s first hydrogen power generation bidding market. Japan has set quotas for cofiring of NH3 (ammonia) and the Japanese companies Kawasaki and IHI have already developed turbines that can be used with 100% hydrogen.

Each of these examples are elaborated in much more detail in the country chapters of the report.

So the report recommends closer dialogue by both policymakers and companies:

Policy makers from all four countries can therefore benefit from exchanging early experiences. Technically, companies from all countries are working on improving existing technologies and innovating new ones to answer to the goals set by their countries politically. Again, knowledge exchange and B2B networking can foster partnerships and potentially speed-up innovation processes.

7. Green iron and steel

Iron and steel sectors are significant sources of carbon emissions in all of these countries. The report explains that “Australia is the greatest iron ore producer globally, with its exports continuing to grow. Meanwhile, Japan, Korea, and Germany are the 3rd, 5th, and 8th largest producers of steel globally.”

A growing number of iron and steel companies are committing to reducing direct emissions from their production processes. What’s more, because steel is a crucial part of other important sectors, these companies are under pressure from their customers and governments in export markets to cut their emissions. Hydrogen is seen as a key application for doing exactly that.

This mutual interest and dependency create a fruitful ground for a deepening of the cooperation between mining businesses in Australia and steel producers in Germany, Japan, and Korea. Understanding each other's ambitions and needs can contribute to a smoother transition…Relevant agreements and collaborations can be set up early now so that companies from each country can benefit from each other’s expertise and strong consortia can be formed. Since green steel will remain more expensive than conventional steel for the time being, policymakers from the four countries could align their incentive structures and start joint funding initiatives. While any shifts in the steel value chain need to be carefully considered, they might offer new, future-proof business models, where being among the first-movers offers great opportunities for the countries and businesses involved

The report is much more detailed than my summary can do justice. Again, anyone interested in these issues should take a look at the report itself.

…but skepticism is still warranted

All of that being said, there are level-headed and serious energy experts who are skeptical about this whole business of international hydrogen trade. A prominent example is Anne-Sophie Corbeau at the Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia University, who wrote in Cipher that, because hydrogen is really hard to transport and store, there probably won’t be a rational business case for importing it:

The real question is what makes most economic sense globally. Ultimately, it may not pencil out to transport hydrogen long distances to consume it in the industrial sector at all. The landed price could likely be significantly higher than in the exporting country. In fact, it may make more sense for would-be hydrogen exporting countries to produce and export semi-finished industrial products made with hydrogen instead, such as those needed in the steelmaking process. This approach could address one potential disappointment would-be exporters may eventually face: Hydrogen is not the new oil and won’t generate the same rents. But clean hydrogen could spur industrial development in these countries.

I must confess I’m in the same camp as Corbeau here.